Introduction to Hard Cheeses at the Art of Cheese in Longmont, CO

When we chose to come out to Longmont, CO, we had no idea that there would be a cheese school 15 minutes from our rental. What an amazing bonus for our stay here! Neil and I have “dipped our toes” into cheesemaking but just handful of times so when we found out we could attend Cheesemaking classes, we figured it was our duty as cheeselovers. Our friend Jinnee was in town when the class occurred, so we all attended together. Jinnee said, “I love hanging out with you guys, we always eat so well!”

The class occurred on a Sunday afternoon at Briar Gate Farm in Longmont, CO. Kate Johnson, founder of The Art of Cheese would be our teacher that day and gave us a little history to get started. She and her family bought the farm about 15 years ago so they could live in the country and raise horses. One day they decided to purchase goats and got hooked. When you have goat moms and goat babies you have a lot of milk and with a lot of milk, you decide to make cheese because there’s just so much milk! When Kate started looking around for cheesemaking classes in the area, there were none to be found so she opened The Art of Cheese. This was about 5 years ago and they happily just opened a new classroom on the farm so they could offer more classes.

When planning out cheese classes, Kate bases them on the equipment you’ll need, the number of ingredients and how soon you have to wait to eat your cheese. She explained that this would be considered an intermediate level class and although Jinnee had never made cheese, she was ready to begin! We’d be making Guido’s cheese which can be compared to a parmesan style cheese. Check out the recipe at the end of the entry if you want to try to make your own. It would take about a month to age at 50-55 degrees but if you keep it in your regular refrigerator it will take a few extra weeks.

There are four basic ingredients involved in many cheese recipes. Milk is the biggest one! And it’s pretty important to consider the quality and processes used on the milk when picking up your gallon. Milk is made from proteins, butterfat and calcium, these all play a big role in making cheese. Have you heard of raw milk? Or do you prefer pasteurized milk? Raw milk is straight from the cow but has had much discussion around if it’s safe or not. Pasteurized milk gets heated to a temperature where the bacteria will be destroyed. What about Homogenized, what is that? Its when all the fat globules in the milk are processed to become the same size. You don’t have to do that to goats milk though because it naturally occurs that way. That’s why it’s easier to digest than cow’s milk.

We don’t want to spend the entire entry talking about milk though, just keep in mind that you can make cheese from pasteurized or raw milk but your recipe may call for one specifically. Also be sure to use whole milk or “cream on top” milk as opposed to a low-fat milk because you want all the fat you can get to make your cheese. And a very important note, don’t buy Ultra-Pasteurized milk because it’s heated so much that it wants to stay milk and not turn into cheese. We learned this lesson when we made cheese with Lexi and Alex, https://wineandcheesefriday.com/making-goat-cheese-with-lexi-and-alex/. And if you’re using grocery store milk, you can add Calcium Chloride to restore the Calcium lost during the pasteurization of the milk.

The other ingredients used in cheesemaking are a bacteria culture, rennet and salt. The bacteria can be either mesophilic, active under 100 degrees F or thermophilic, active over 100 degrees F and will depend on your recipe. If you want to start making cheese, there are tons of supplies available from New England Cheesemaking Supply Company! You’ll also need some rennet which is an enzyme that comes from animal stomachs. It causes the milk to coagulate into curds and whey. If you’re vegetarian, don’t worry, there’s a vegetarian rennet that is made from mushrooms.

There are a few specifics you should know about your rennet other than animal vs vegetable. Be sure to use distilled or filtered water that is free from chlorine to dilute your rennet. Also vegetarian rennet is usually double the strength of animal rennet so be sure to adjust your recipe. It’s also very important to check the expiration date on your rennet because if it’s expired your cheese won’t turn out right. If you are concerned that your rennet will expire too quickly you can use a frozen version instead. It is sold as tablets but your dose will need to be adjusted with these too.

The final ingredient, salt, plays an equally important role as the above. It contributes to flavor, preservation and the chemistry of the cheese. Be sure to use non-iodized salt or you can find something specifically called “cheese salt”.

I realize this is a lot of information but since you’re going to wait a month to eat your cheese, you want to be sure you make it properly :) You can also use something called a “make sheet” where you can jot down notes such as mistakes, alterations, or just general notes about the day when you made your cheese. It will help you remember or maybe create some happy mistakes to make your cheese even tastier.

So how do you make the cheese? Well I already mentioned that the recipe will be at the end but you basically cook your milk, either for a long time or not, add your bacteria and rennet, stir it all together, wait some time, cut your curds and press them. There’s actually a lot of time involved in some recipes so you might get to experience the “Monotony of Cheesemaking!” But don’t worry, some cheeses have a lot less steps and you can eat it that day.

During our class we made a batch of cow’s milk from the grocery store and another batch of Briar Gate Farm goat’s milk so we could see how they look a little different, and cook a little different. Everyone in class took turns measuring, stirring, looking for the correct temperature and keeping it at that temp, and then “cutting the curds.”

“Cutting the curds” was an interesting technique. You need to make a tiny slice in your cooked milk and then try to lift under the slit to see that the milk has solidified. Then you make vertical lines in the solid mass so that it looks like a checkerboard. This is only one direction of cutting the curd though, then you have to use a slotted spoon to make the horizontal cuts. You basically scoop under the curds just by feel starting at the top and then continuing down. Then the curds will start to move around in the pot so you can see their approximate size.

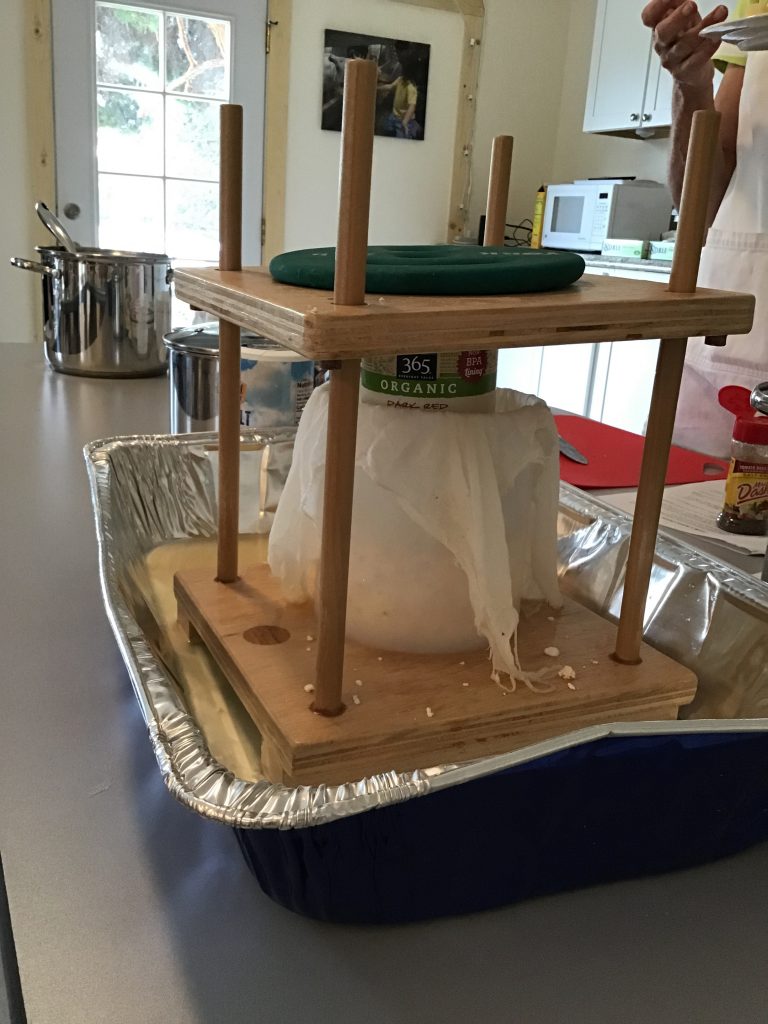

The final step in this “cheese make” is to drain and press the curds. Be sure the curds are still warm when you press them! The curds get scooped into a “form” which will create the shape of the cheese. The follower pushes the curds in the form to squeeze out the whey and solidify the cheese. When making this cheese at home you will need both the form and the follower.

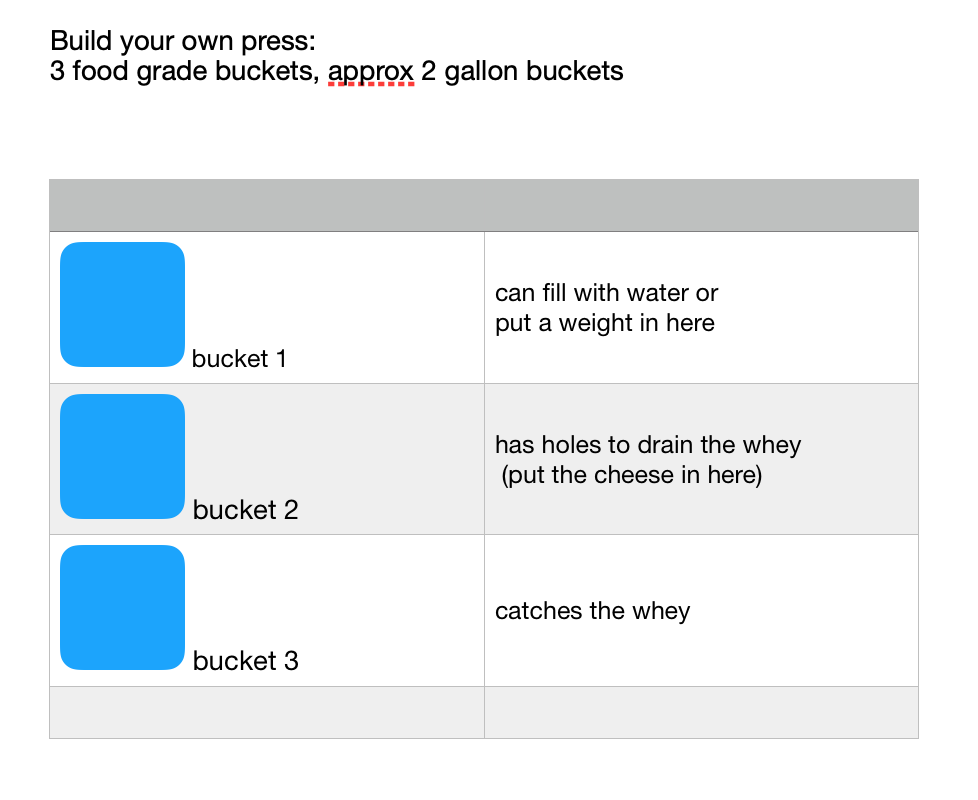

There are a few types of press though. The press applies the weight on the cheese forms. There are cheese presses that can be purchased with nuts and threaded rods to adjust the pressure. If you’re just starting and you want to create your own press, you can used food grade buckets filled with water. See the image below.

Making cheese creates a lot of excess whey. It can just be dumped down the drain but can be used in soup, bread making, or given to hog farmers as feed. It can even be frozen into cubes to save for recipes. You can also put it on your tomato plants for nutrients. Just a few ideas if you’re wondering what to do with all that liquid draining out.

Throughout the class, we also got to taste some Guido cheese that was all ready to eat. There was even some Pinot Noir #wineandcheese!

Waxed plain Guido Vacuum-sealed Guido with cumin seasoning Vacuum-sealed Guido with ground espresso plain Guido with a natural rind fresh curds from our cheese make

All of the cheese we tasted that day were made from store bought cow’s milk. The waxed cheese smelled like milk and was a little tart. The guido with cumin spice smelled and tasted like cumin. It had such a great flavor! We could smell the espresso in the next cheese and it tasted a little chocolatey. The natural rind had a little bit of mold on the exterior but Kate let us know, that’s ok, and she just cut it off. The flavor of the cheese was pretty dry but more buttery than the waxed version.

Neil and I tried Wisconsin cheese curds when we were at the Mall of America last summer but didn’t really understand all the excitement. We still gave the curds a taste and although they were squeaky, you could taste the milk too. We liked them better than our first experience but these were curds more in the “raw” sense of the word. Cheese curds are usually part of the cheddaring process which we’ll discuss in another entry.

You may have noticed that the cheeses we tasted in class had some “additives” like spice, espresso, etc. We discussed how to incorporate these “extras” into the cheese during class too. If you want to add something to the cheese it would have to be sustainable at 50-55 degrees, since this is the temperature the cheese will age. You can add these flavors direct to the pot of curds before scooping them into the form.

Our final hands on activity of the class was “waxing the cheese!” Kate had made some wheels of Guido cheese a few days before so they would be solidified and ready to bring home. In order to help the cheese age at home, we would dip the wedge in food grade wax. There were multiple colors of wax in crockpots and we could choose red, orange, white or black. Neil and I decided to use red and orange for the “spicy” cheese that had chipotle spice added to the curds. We got to take home a plain guido too and used the black and white wax. As we mentioned at the beginning, we’d need to wait around a month before we could taste these wedges. Time to practice our patience!

Before the class was over, we made our way outside to see the animals. They produced the milk after all so let’s go learn about them too. There were two main types of goats at Briar Gate Farm, Nubian and Nigerian Dwarf. Nubian goats have floppy ears that hang down and we’ve seen them at a few goat dairies that we’ve visited.

The goats had color coordinated collars to show which breeding generation they were from. When breeding goats, Kate looks for three qualities; the goat’s temperament, shape of the teat, and size of opening on the teat for milk. This all comes from experience but since they are dairy goats, these are all important.

The goats need to be milked twice per day for part of the season and once during the other stage. All of these goats have recently have had a baby and if you’re wondering the goat gestation cycle lasts about 5 months. The baby goats usually nurse for about 3 months and then they are weaned off. There’s still plenty of milk for cheese though and we got to see the milking station off to the side.

Wow, it’s hard to believe this was all in one afternoon! We learned about cheese, made cheese, ate cheese, and met the goats. Definitely packed full! And if you’ve been watching our social media, you know that one class wasn’t enough for me so there will be more entries to learn even more about cheesemaking! Thanks to Kate and the Art of Cheese for creating such a fun activity and being available for all the budding cheesemakers out there.

permission to print the recipe given to WineAndCheeseFriday by The Art of Cheese:

Guido’s Italian Cheese

Equipment Needed: Stainless Steel Pot (1 Gallon) w/ lid Slotted Spoon Cheese thermometer Cheesecloth Large Knife Cheese Mold (or cheese baskets) Bowl or pot to catch the whey 2-3 pound weight Dorm refrigerator (for aging your cheese)

Ingredients: Fresh or store-bought whole milk, pasteurized (goat’s or cow’s milk) Thermophilic Starter Culture (can be ordered from various cheese supply companies) Rennet Cheese salt (or non-iodized sea salt)

This recipe is adapted from a recipe submitted by a home cheese maker, Guido Giuntini, to the Home Cheese Making book by Ricki Carroll. It’s a nice Italian hard cheese that is very easy to make and uses minimal equipment along with a short aging time.

1. Heat 1 gallon of whole milk to 90 degrees, and then add ½ packet (or 1/8 tsp) of direct-set Thermophilic starter culture. Mix thoroughly and let set for 30 minutes.

2. Dilute ½ tsp of liquid rennet (or ½ tablet) in ¼ cup cool non-chlorinated water and add to the ripened milk. Stir and let set for 15 minutes.

3. Cut the curd with a long knife into ¼ inch cubes.

4. Stirring frequently, slowly heat the curds to 120 degrees over a period of 30-40 minutes.

5. Line a cheese mold (or cheese baskets) with cheesecloth, set into a bowl or pot, and ladle the curds into the mold (if you’d like to make a flavor variety such as cumin or espresso, add the ingredient to the curds before you fill the mold). For cheese baskets, each basket will hold ½ gallon milk so you can stack w baskets, then put a third on top with a weight on it.

6. Set the mold’s follower (or another basket) onto the cheese, add a can if necessary, and put a 2-3 pound weight on top. Wait 15 minutes.

7. Take the cheese out of the mold, unwrap, turn over, rewrap and put back in the mold with the weight on top. Do this again for 15 minutes, then for 30 minutes, and then for 1 hour, or until the rind of the wheel of cheese has closed.

8. Eventually, let the cheese set with a 2 pound weight for 12-24 hours.

9. Combine 1/4 pound (4 oz) of cheese salt with 1 quart (4 cups) of water to make a brine solution. Remove the cheese from the mold and place in the brine solution. Let set for about 12 hours (more for bigger wheels, less for smaller wheels).

10. Remove cheese from brine and pat dry with paper towels. (boil the brine and strain it; then refrigerate for later use.)

11. Place the cheese on a cheese mat in a container in a cool place for 3 weeks (a dorm fridge turned to the warmest temp. approx. 50-55 degrees, works well).

12. For the first week, turn the cheese 2-3 times a day. After that, turn it once a day.

13. At three weeks, slice the cheese and enjoy. Guido recommends serving it as an after dinner treat with a bit of honey on top and a class of Chianti!